In the introduction to her 1983 book The Puritan Conversion Narrative: The Beginnings of American Expression, Patricia Caldwell maps out some significant differences between British and American conversion narratives. According to her, the experience of conversion for English converts was often conveyed in very personal terms: women and men used childbirth and deliverance literally and figuratively to explain their new-found sense of godliness. Further, when they described their experience, it was often expressed in terms of movement down into and out of the body and selfhood. Dreams and visions also played a frequent role (recall that in Grace Abounding Bunyan records a dream he had). These British narratives usually contained a sense of closure, an end to striving, their authors expressing a yearning for refuge, solace, and a happy ending (i.e., heavenly assurance).

American narratives, by contrast, omitted the language of childbirth and deliverance. In place of the movement away from the body and the self, these narratives often referred to travel and migration; converts often recalled their actual experience of migration to New England as a central moment in their experience, and they often wrote and/or spoke in terms of a movement across physical and spiritual geography. Unlike many of the British texts, American converts often closely tied their narratives to Scripture, with biblical verses often becoming structural elements of the narrative. Lastly, after the literal and figurative movement experienced by the congregants, a feeling of discontent, dissatisfaction, and unfulfilled spiritual desire (i.e., no heavenly assurance) remained with them. Thus, Thomas Shepard's constant doubts about his soul's status and Anne Bradstreet's perplexity over failing to feel a sense of "constant joy in my pilgrimage and refreshing which I supposed most of the servants of God have" (from "To My Dear Children") was common to many New England Puritans.

Caldwell reminds us that a genre which might on the surface appear to be homogeneous in reality contains diverse and complex elements.

Friday, September 30, 2011

Class Recap 9/28

|

| Old Burying Ground, Cambridge, Massachusetts---Thomas Shepard is believed to be buried here among his congregants |

Before turning to Thomas Shepard and John Bunyan, the class returned to Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation (1630-1650) and Thomas Morton's New English Canaan (1637). When considering Shepard and his congregants, we took up issues such as the genesis of the private individual, selfhood and identity, self-determination and godly dependence, and Shepard as Puritan and Christian. John Bunyan's Grace Abounding (1666) raised questions about literary publication and manuscript culture, the rise of personal writings and issues of genre, the use of language and metaphor, and the expression of sincerity (and thus emotion in general) through the written word.

It is worth remembering that the 1994 edition of God's Plot: Puritan Spirituality in Thomas Shepard's Cambridge reprints an abridged version of the Journal and a selection of the Confessions. Those wishing to investigate these texts in full should turn to the 1972 edition of God's Plot (for the Journal) and the original 1981 and 1991 publications of the Confessions.

Sunday, September 25, 2011

"Mixtures Pernicious," Being a Further Commentary on Literary Transatlanticism

In addition to the reference to Sir Henry Vane, Thomas Shepard mentions a number of other prominent Puritans, including Nathaniel Ward (1578-1652), another transatlantic figure. Ward was fifty-five when he emigrated to Massachusetts in 1634 after Laud deprived him of his pulpit. He became the minister at Ipswich, the home of Simon and Anne Bradstreet (and Governor Winthrop's son, John, Jr.). In 1641, he was tapped to draw up Massachusetts Bay's Body of Liberties, which built upon but somewhat softened an earlier draft written by John Cotton.

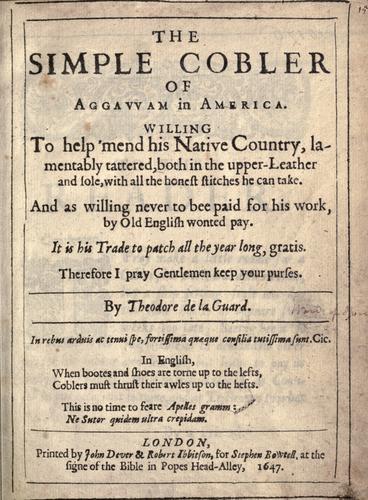

Ward is most famous for his second book, The Simple Cobler of Aggawam in America (1647). Published in England, this book is often cited as the first book of American humor (albeit a dark, satirical humor remeniscent of the Marprelate Tracts). Note that while the title page states the Cobbler is "of" Aggawam (the Indian name for Ipswich), England is nevertheless called his native country, even though Ward had been living in the New World for over a decade at the time of the book's publication. Note, too, that while he published anonymously under the appropriately named "Theodore de la Guard," Ward was generally known as the author. The Simple Cobler rails against the newest fashions, from women's immodest clothing to the spectre of religious toleration. According to Ward,

Ward is most famous for his second book, The Simple Cobler of Aggawam in America (1647). Published in England, this book is often cited as the first book of American humor (albeit a dark, satirical humor remeniscent of the Marprelate Tracts). Note that while the title page states the Cobbler is "of" Aggawam (the Indian name for Ipswich), England is nevertheless called his native country, even though Ward had been living in the New World for over a decade at the time of the book's publication. Note, too, that while he published anonymously under the appropriately named "Theodore de la Guard," Ward was generally known as the author. The Simple Cobler rails against the newest fashions, from women's immodest clothing to the spectre of religious toleration. According to Ward,

Ward is most famous for his second book, The Simple Cobler of Aggawam in America (1647). Published in England, this book is often cited as the first book of American humor (albeit a dark, satirical humor remeniscent of the Marprelate Tracts). Note that while the title page states the Cobbler is "of" Aggawam (the Indian name for Ipswich), England is nevertheless called his native country, even though Ward had been living in the New World for over a decade at the time of the book's publication. Note, too, that while he published anonymously under the appropriately named "Theodore de la Guard," Ward was generally known as the author. The Simple Cobler rails against the newest fashions, from women's immodest clothing to the spectre of religious toleration. According to Ward,

Ward is most famous for his second book, The Simple Cobler of Aggawam in America (1647). Published in England, this book is often cited as the first book of American humor (albeit a dark, satirical humor remeniscent of the Marprelate Tracts). Note that while the title page states the Cobbler is "of" Aggawam (the Indian name for Ipswich), England is nevertheless called his native country, even though Ward had been living in the New World for over a decade at the time of the book's publication. Note, too, that while he published anonymously under the appropriately named "Theodore de la Guard," Ward was generally known as the author. The Simple Cobler rails against the newest fashions, from women's immodest clothing to the spectre of religious toleration. According to Ward, "The power of all Religion and Ordinances, lies in their purity: their purity in their simplicity: then are mixtures pernicious. I lived in a City, where a Papist preached in one Church, a Lutheran in another, a Calvinist in a third; a Lutheran one part of the day, a Calvinist the other, in the same pulpit: the Religion of that place was but motley and meagre, their affections Leopard-like. . ."

In response to this "poly-piety," he grimly remarks "I dare take upon me, to bee the Herauld of New-England so farre, as to proclaime to the world, in the name of our Colony, that all Familists, Antinomians, Anabaptists, and other Enthusiasts shall have free liberty to keepe away from us, and such as will come to be gone as fast as they can, the sooner the better. . ."

Ward moved back to England in 1647 (after the book's publication). The book's title page shows the Simple Cobbler was printed for Stephen Bowtell, who also had printed Anne Bradstreet's The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung up in America (1650). Ward likely had a hand in the publication of The Tenth Muse, and one of his poems appears among the introductory verses; in it he refers to Bradstreet as a "right Du Bartas girl." (Guillaume de Salluste Du Bartas was a sixteenth-century French Huguenot poet and a significant influence on Bradstreet's early poetry.)

Ward did not approve of mistreating the King (and likely rejected regicide), and despite his literary celebrity as the Simple Cobbler, he settled into the ministry of a small English parish, going to his eternal reward in 1652.

A Transatlantic Literary Connection

In Shepard's autobiography you will notice a reference to Sir Henry Vane, "too suddenly chosen governor" (67) of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Shortly after the Antinomian crisis described by Shepard, Vane returned to England where, as a member of parliament, he became an advocate of religious toleration and separation of church and state. In 1653 Milton wrote a sonnet praising Vane for, among other things, his understanding of "both spirituall powre & civill, what each meanes / What severs [i.e., limits, sets the boundaries of] each." Milton chose not to publish this poem, nor two others paying tribute to figures of the English revolution (Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell), in his 1673 Poems, because of its connection to Vane, who was executed by Charles II in 1662. Milton's sonnet was published posthumously in 1694.

When the sonnet came to England in the sixteenth century, it was a love lyric. Poets like Donne and Herbert used it for devotional poems, and Milton expanded the form further by using it to write about public figures and political topics as well.

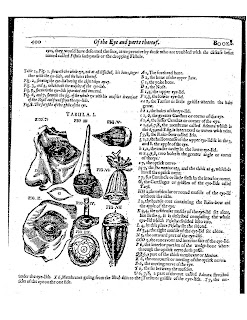

Milton's most famous sonnet, "When I Consider How My Light Is Spent" (c. 1652), has different kind of connection to Shepard's autobiography. Shepard tells of the loss and restoration of his infant son's vision. Interpreting this event as God's work, Shepard turns it into an admonishment to the son to "remember to lift up thy eyes to heaven" and "take heed thou dost not make thy eyes windows of lust" (39). Milton, who lost his vision in his early forties, also uses blindness as the starting point for a conversation about God's plan for him in this poem. In another sonnet, he attributes the loss of his sight to having "overply'd" his eyes "in libertyes defence." (He also withheld this poem from publication, probably because of its reference to his part in the revolution.) We will see how Milton's blindness becomes symbolic in Paradise Lost also. Does interpreting literal, worldly experiences as expressions of divine will seem different in a self-consciously literary work than it does in an autobiography?

When the sonnet came to England in the sixteenth century, it was a love lyric. Poets like Donne and Herbert used it for devotional poems, and Milton expanded the form further by using it to write about public figures and political topics as well.

|

| Parts of the eye, from a 1631 anatomy text. |

Milton's most famous sonnet, "When I Consider How My Light Is Spent" (c. 1652), has different kind of connection to Shepard's autobiography. Shepard tells of the loss and restoration of his infant son's vision. Interpreting this event as God's work, Shepard turns it into an admonishment to the son to "remember to lift up thy eyes to heaven" and "take heed thou dost not make thy eyes windows of lust" (39). Milton, who lost his vision in his early forties, also uses blindness as the starting point for a conversation about God's plan for him in this poem. In another sonnet, he attributes the loss of his sight to having "overply'd" his eyes "in libertyes defence." (He also withheld this poem from publication, probably because of its reference to his part in the revolution.) We will see how Milton's blindness becomes symbolic in Paradise Lost also. Does interpreting literal, worldly experiences as expressions of divine will seem different in a self-consciously literary work than it does in an autobiography?

Friday, September 23, 2011

The Approach of Grace and the Challenges of Conversion

On September 28, the class will look at Thomas Shepard's autobiography and journal, his transcriptions of his parishioners "evidence" of conversion, and John Bunyan's Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners (1666). The conversion experience was a key spiritual moment for Puritans and the examination process a significant point of contention between English and New English Puritans.

Like Hooker (and John Cotton) before him, Shepard was driven from the pulpit by Archbishop Laud and his pursuit of religious conformity. (Laud is pictured in Sir Anthony Van Dyck's 1635 portrait.) After travelling to the New World, he succeeded Thomas Hooker as minister in Cambridge after Hooker took his congregation west to Connecticut. Shepard played a key role in the suppression of Anne Hutchinson during the Antinomian Crisis in Massachusetts and was considered a rising star among the ministry at his untimely death at the age of 43. Several of his sons followed their father into the ministry, including Thomas Shepard, Jr., whose "Eye-Salve" is considered a major late 17th century New England sermon.

Like Hooker (and John Cotton) before him, Shepard was driven from the pulpit by Archbishop Laud and his pursuit of religious conformity. (Laud is pictured in Sir Anthony Van Dyck's 1635 portrait.) After travelling to the New World, he succeeded Thomas Hooker as minister in Cambridge after Hooker took his congregation west to Connecticut. Shepard played a key role in the suppression of Anne Hutchinson during the Antinomian Crisis in Massachusetts and was considered a rising star among the ministry at his untimely death at the age of 43. Several of his sons followed their father into the ministry, including Thomas Shepard, Jr., whose "Eye-Salve" is considered a major late 17th century New England sermon.

Like Hooker (and John Cotton) before him, Shepard was driven from the pulpit by Archbishop Laud and his pursuit of religious conformity. (Laud is pictured in Sir Anthony Van Dyck's 1635 portrait.) After travelling to the New World, he succeeded Thomas Hooker as minister in Cambridge after Hooker took his congregation west to Connecticut. Shepard played a key role in the suppression of Anne Hutchinson during the Antinomian Crisis in Massachusetts and was considered a rising star among the ministry at his untimely death at the age of 43. Several of his sons followed their father into the ministry, including Thomas Shepard, Jr., whose "Eye-Salve" is considered a major late 17th century New England sermon.

Like Hooker (and John Cotton) before him, Shepard was driven from the pulpit by Archbishop Laud and his pursuit of religious conformity. (Laud is pictured in Sir Anthony Van Dyck's 1635 portrait.) After travelling to the New World, he succeeded Thomas Hooker as minister in Cambridge after Hooker took his congregation west to Connecticut. Shepard played a key role in the suppression of Anne Hutchinson during the Antinomian Crisis in Massachusetts and was considered a rising star among the ministry at his untimely death at the age of 43. Several of his sons followed their father into the ministry, including Thomas Shepard, Jr., whose "Eye-Salve" is considered a major late 17th century New England sermon.As you read, consider how Bunyan's life experiences and eventual conversion compare with Shepard's. Additionally, how do their spiritual experiences compare to Shepard's less educated congregants?

Class Recap 9/21

We began class on September 21 by returning to Thomas Hooker's sermon "The Danger of Desertion" (1641) examining its structure and use of typology as well as the genre of the jeremiad. Josias Nichols's "Plea of the Innocent" (1602) was considered in relation to Hooker's piece, and the class investigated Nichols's contention that the word Puritan is a misnomer for those who advocate for further reform of the English church.

We began class on September 21 by returning to Thomas Hooker's sermon "The Danger of Desertion" (1641) examining its structure and use of typology as well as the genre of the jeremiad. Josias Nichols's "Plea of the Innocent" (1602) was considered in relation to Hooker's piece, and the class investigated Nichols's contention that the word Puritan is a misnomer for those who advocate for further reform of the English church. The remainder of the class was spent with William Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation (1630-1650). After a brief discussion of the beginnings of the Reformation in England, we took up the questions of what Of Plymouth Plantation reveals about Puritanism and how Bradford's Puritanism influenced his task as historian. We also considered Bradford's aesthetic goals as he wrote his book, including his deployment of the plain style as an artistic choice as well as an economic countermeasure (via Michelle Burnham's scholarship. Class ended with an interrogation of the Other in Bradford, focusing first on his comments upon European-Native American interaction.

On September 28, we shall briefly return to this question of the Other in Bradford to think about Otherness as not just a racial category. What Others appear in Of Plymouth Plantation? Further, how is Thomas Morton's New English Canaan in dialogue with Puritanism?

Some other questions to raise about Bradford's book which time did not allow us to investigate: What is the relationship between Part I and Part II of the history? How does the text challenge commonly held images of the Pilgrim Founders? What does one make of Bradford's inclusion of the colony's criminal activity?

The painting is by Michel Felice Corne (1752-1815), completed during the years 1803-1806 (and based upon a 1799 engraving). Since Bradford's manuscript was not recovered and printed until the mid-1850s, Corne would not have had access to his descriptions of the first landing and settlement. A simple Google search will uncover a number of similar paintings, many of them collected on the Pilgrim Hall Museum web site. Consider such representations in relation to the question above about commonly held ideas about the Pilgrims. (One might start by noticing that Corne has his Pilgrims wearing late 18th century trousers, not 17th century garb.)

Some other questions to raise about Bradford's book which time did not allow us to investigate: What is the relationship between Part I and Part II of the history? How does the text challenge commonly held images of the Pilgrim Founders? What does one make of Bradford's inclusion of the colony's criminal activity?

The painting is by Michel Felice Corne (1752-1815), completed during the years 1803-1806 (and based upon a 1799 engraving). Since Bradford's manuscript was not recovered and printed until the mid-1850s, Corne would not have had access to his descriptions of the first landing and settlement. A simple Google search will uncover a number of similar paintings, many of them collected on the Pilgrim Hall Museum web site. Consider such representations in relation to the question above about commonly held ideas about the Pilgrims. (One might start by noticing that Corne has his Pilgrims wearing late 18th century trousers, not 17th century garb.)

Sunday, September 18, 2011

Some Reflections on Puritanism and Authority

Toward the end of our discussion of Twelfth Night we began to consider whether Malvolio might represent some larger human social principle or pattern (rather than the more topical Puritan). This question returns to some issues indirectly raised in the previous class - does the fact that the term "puritan" now refers to so much beyond its original historical context suggest that puritanism itself is a recurring cultural identity?

If so, this identity may have something to do with a way of internalizing authority. Shakespeare's comedies typically leave behind or bracket a world of patriarchal social authority - the main action takes place in a youthful fantasy world in which existing social relationships are challenged and rearranged. Only at the end are the old world and the old form of authority restored, usually with some kind of transformation. You can see this pattern clearly in A Midsummer Night's Dream and As You Like It. Twelfth Night has the same structure: Olivia's father and brother, as well as Sebastian and Viola's father, are dead, and the "children" are taken to a confusing, foreign world where they have to figure out their own social relationships. (Similarly with the American colonists?) Orsino should be the reigning patriarchal authority in this world, but in the first scene he abdicates his power fairly explicitly, effectively becoming just another child at play, and does not resume it until the very end of the play.

Malvolio, then, might represent an attempt at self-discipline through repression of pleasure, in the absence of an authority to enforce the social order from the top down. Olivia seems to have turned over the ordering of her house to Malvolio after the loss of her father and brother. In a way, Malvolio is trying to internalize the lost patriarchal authority - that is how he can imagine himself as an appropriate husband for Olivia.

As we continue our reading this semester, consider how these Puritan writers relate to external or worldly authority and how they create authority internally.

If so, this identity may have something to do with a way of internalizing authority. Shakespeare's comedies typically leave behind or bracket a world of patriarchal social authority - the main action takes place in a youthful fantasy world in which existing social relationships are challenged and rearranged. Only at the end are the old world and the old form of authority restored, usually with some kind of transformation. You can see this pattern clearly in A Midsummer Night's Dream and As You Like It. Twelfth Night has the same structure: Olivia's father and brother, as well as Sebastian and Viola's father, are dead, and the "children" are taken to a confusing, foreign world where they have to figure out their own social relationships. (Similarly with the American colonists?) Orsino should be the reigning patriarchal authority in this world, but in the first scene he abdicates his power fairly explicitly, effectively becoming just another child at play, and does not resume it until the very end of the play.

Malvolio, then, might represent an attempt at self-discipline through repression of pleasure, in the absence of an authority to enforce the social order from the top down. Olivia seems to have turned over the ordering of her house to Malvolio after the loss of her father and brother. In a way, Malvolio is trying to internalize the lost patriarchal authority - that is how he can imagine himself as an appropriate husband for Olivia.

As we continue our reading this semester, consider how these Puritan writers relate to external or worldly authority and how they create authority internally.

Recap of 9/14 Class

We began with a brief sketch of the Puritans' status in England from the accession of Elizabeth I until the closing of the theaters in 1642. (See the chronology on the handout, available on e-learning.) The class then enumerated Stubbes's reasons for opposing the theater as outlined in The Anatomy of Abuses, and looked at an excerpt from William Prynne's antitheatrical tract Histriomastix as well as another passage from Stubbes on stage transvestism. We also briefly examined some theatrical language in Paradise Lost, looking forward to Milton's ambivalence on this matter.

Next we looked at a version of the stage Puritan in the earliest commercially successful American comedy, The Contrast by Royall Tyler, remarking on the character's inferior social status and gullibility. From there we moved to a discussion of Twelfth Night, after viewing scenes 1.5 and the end of 5.1 in the Trevor Nunn film. Our discussion focused on ways to integrate the Malvolio/Puritan plot into the play's larger themes.

Finally we began discussing Thomas Hooker's jeremiad on the state of England shortly before his departure for New England. We will continue talking about this sermon on Wednesday, so please review the text before class.

Next we looked at a version of the stage Puritan in the earliest commercially successful American comedy, The Contrast by Royall Tyler, remarking on the character's inferior social status and gullibility. From there we moved to a discussion of Twelfth Night, after viewing scenes 1.5 and the end of 5.1 in the Trevor Nunn film. Our discussion focused on ways to integrate the Malvolio/Puritan plot into the play's larger themes.

Finally we began discussing Thomas Hooker's jeremiad on the state of England shortly before his departure for New England. We will continue talking about this sermon on Wednesday, so please review the text before class.

Thursday, September 15, 2011

New England, New Challenges

For the class of the 21st we'll be focusing primarily on the founding of Plymouth Colony as seen through the eyes of William Bradford, the colony's second (and often re-elected) governor. As you read, consider the following questions: How does Bradford's Puritanism inform his historicism? That is, what sort of history does Bradford produce as a result of his Puritanism? How does his Puritanism influence the content of his history?

For the class of the 21st we'll be focusing primarily on the founding of Plymouth Colony as seen through the eyes of William Bradford, the colony's second (and often re-elected) governor. As you read, consider the following questions: How does Bradford's Puritanism inform his historicism? That is, what sort of history does Bradford produce as a result of his Puritanism? How does his Puritanism influence the content of his history?An alternate perspective concerning events at Plymouth Colony is found in Thomas Morton's New English Canaan, published in 1637 in London. Thomas Morton was an Anglican and a staunch Royalist in his politics. He settled at Merrymount, near Quincy, Massachusetts (south of Boston but north of Plymouth). In its entirety, Morton's book is considerably shorter than Bradford's history; it is divided into three parts, and it comments upon the plant and animal life as well as the human inhabitants of New England. The brief excerpt assigned from New English Canaan involves Morton's ("Mine Host") interaction with the Puritans, especially with regard to the incident of the maypole at Merrymount. You'll want to compare Morton's narration of the incident with Bradford's. What is Morton's aim in publishing his book?

Nathaniel Hawthorne later immortalized this incident in his short story "The May-Pole of Merry Mount," published in 1835. Of Plymouth Plantation was not published until the middle of the nineteenth century, but excerpts of it did appear in New Englands Memoriall, a book published in 1669 by William Bradford's nephew, Nathaniel Morton (no relation to Thomas Morton). Hawthorne drew on Bradford's version of events when he composed his short story.

Sunday, September 11, 2011

Puritan Antitheatricalism

This is Nigel Hawthorne as Malvolio in a 1996 film version of Twelfth Night directed by Trevor Nunn. As you can see from Malvolio's costume, Nunn puts the play in a Victorian setting. Scott's remark last week that by "Puritan" we often really mean "Victorian" made me realize why this setting works so well. (I like the movie - Ben Kingsley is the perfect Feste.)

For Wednesday you will read among other things a brief excerpt from Philip Stubbes' Anatomy of Abuses (1583). The book is in the form of a dialogue between Philoponus, a worldly traveler, and Spudeus, an uneducated yokel. They are talking about England (a foreign land to them) and its social customs. The critique is scathing and wide-ranging, from bear-baiting, women's fashion, gambling, drunkenness, and "tennisse," to swearing, usury, covetousness, and maypoles. (Recall Earle's jab about maypoles in the character of the "shee-hypocrite.") You'll just read the section on stage plays - what is it that makes plays evil to Stubbes? Is it just a matter of resenting enjoyment?

If you are interested in the topic of antitheatricalism, I highly recommend The Antitheatrical Prejudice by Jonas Barish (Berkeley, 1981). The whole book is great - it goes from Plato to Ivor Winters - but there are two chapters on Puritanism. I've uploaded these to the "Recommending Readings" folder on e-learning.

For Wednesday you will read among other things a brief excerpt from Philip Stubbes' Anatomy of Abuses (1583). The book is in the form of a dialogue between Philoponus, a worldly traveler, and Spudeus, an uneducated yokel. They are talking about England (a foreign land to them) and its social customs. The critique is scathing and wide-ranging, from bear-baiting, women's fashion, gambling, drunkenness, and "tennisse," to swearing, usury, covetousness, and maypoles. (Recall Earle's jab about maypoles in the character of the "shee-hypocrite.") You'll just read the section on stage plays - what is it that makes plays evil to Stubbes? Is it just a matter of resenting enjoyment?

If you are interested in the topic of antitheatricalism, I highly recommend The Antitheatrical Prejudice by Jonas Barish (Berkeley, 1981). The whole book is great - it goes from Plato to Ivor Winters - but there are two chapters on Puritanism. I've uploaded these to the "Recommending Readings" folder on e-learning.

Notes from 9/7

This is the list of descriptions of Puritanism that I wrote on the board as you were sharing your writing in class last Wednesday:

work ethic

manifest destiny

Christ as shepherd

reform doctrine

preaching/preachiness

simplicity/humility

piety

patriarchal God

self-righteousness

images/stereotypes from external observers

restriction of drama

inspired devotional literature

intellectual community

stoicism

fear-based judgment and exclusion

renunciation of pleasure and fun

forcing of Christianity on others

stereotype of unfeelingness, imposed by modern perspective

bible as source of truth

isolation, separateness

political implications of faith

judgment of social difference

attack on witchcraft

right-wing American Christianity

simultaneous isolation and worldly involvement

national identity

transhistorical phenomenon

control and repression

political radicalism

social conservatism

suppressed sexuality/emotional intensity

rhetoric in rapture

justification of anything/everything in the name of God

work ethic

manifest destiny

Christ as shepherd

reform doctrine

preaching/preachiness

simplicity/humility

piety

patriarchal God

self-righteousness

images/stereotypes from external observers

restriction of drama

inspired devotional literature

intellectual community

stoicism

fear-based judgment and exclusion

renunciation of pleasure and fun

forcing of Christianity on others

stereotype of unfeelingness, imposed by modern perspective

bible as source of truth

isolation, separateness

political implications of faith

judgment of social difference

attack on witchcraft

right-wing American Christianity

simultaneous isolation and worldly involvement

national identity

transhistorical phenomenon

control and repression

political radicalism

social conservatism

suppressed sexuality/emotional intensity

rhetoric in rapture

justification of anything/everything in the name of God

Thursday, September 8, 2011

Puritan Writing and Genre

In the first class (9/7) we compared some very different texts: two poems by Anne Bradstreet ("To My Dear and Loving Husband" and "A Letter to her Husband") and the "character" of "A she precise Hypocrite" from John Earle's Micro-cosmographie. I want to comment further on the question of genre, which arose briefly toward the end of class. Lyric poetry was hardly invented by the Puritans, but the English religious lyric did flower in the seventeenth century in part because of the Protestant emphasis on the subjectivity of spiritual experience. (The Bradstreet poems we read seem to me to have an affinity with the poetry of Donne, who liked to combine images of erotic and spiritual love.) Later in the semester when we look at Robinson Crusoe we will consider how the inward mode of lyric (which is also the mode of Puritan spiritual autobiography) took another form in the early novel.

The Character, by contrast, has an obvious affinity with the stage, and some of Earle's portraits may have been based on Shakespearean types such as Falstaff. As we will see this week, Elizabethan plays were a venue for mocking Puritans. This was not just a form of revenge for Puritan antitheatricality. Stage characters are especially suitable for satirizing types based on external behavior and appearance. On the other hand, Shakespeare's plays, particularly Hamlet, are often seen as reflecting or even motivating the developing sense of inwardness in seventeenth-century England. In addition to the issue of Malvolio as a Puritan type, which you will read about this week, consider what Twelfth Night seems to suggest about the relationship between external appearance and inner life.

The Character, by contrast, has an obvious affinity with the stage, and some of Earle's portraits may have been based on Shakespearean types such as Falstaff. As we will see this week, Elizabethan plays were a venue for mocking Puritans. This was not just a form of revenge for Puritan antitheatricality. Stage characters are especially suitable for satirizing types based on external behavior and appearance. On the other hand, Shakespeare's plays, particularly Hamlet, are often seen as reflecting or even motivating the developing sense of inwardness in seventeenth-century England. In addition to the issue of Malvolio as a Puritan type, which you will read about this week, consider what Twelfth Night seems to suggest about the relationship between external appearance and inner life.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)